Years ago, my Medill colleagues and I launched a hyperlocal news website a bit ahead of its time. When Google released Bulletin, the lessons we learned way back when became relevant again. I whipped up an article on our insights with Rich Gordon, and Nieman Lab picked it up. One angle I would have added is that Google is not trying to become a digital destination like GoSkokie was. It wants to fill hyperlocal content holes and work with local publishers that can’t afford to cover them.

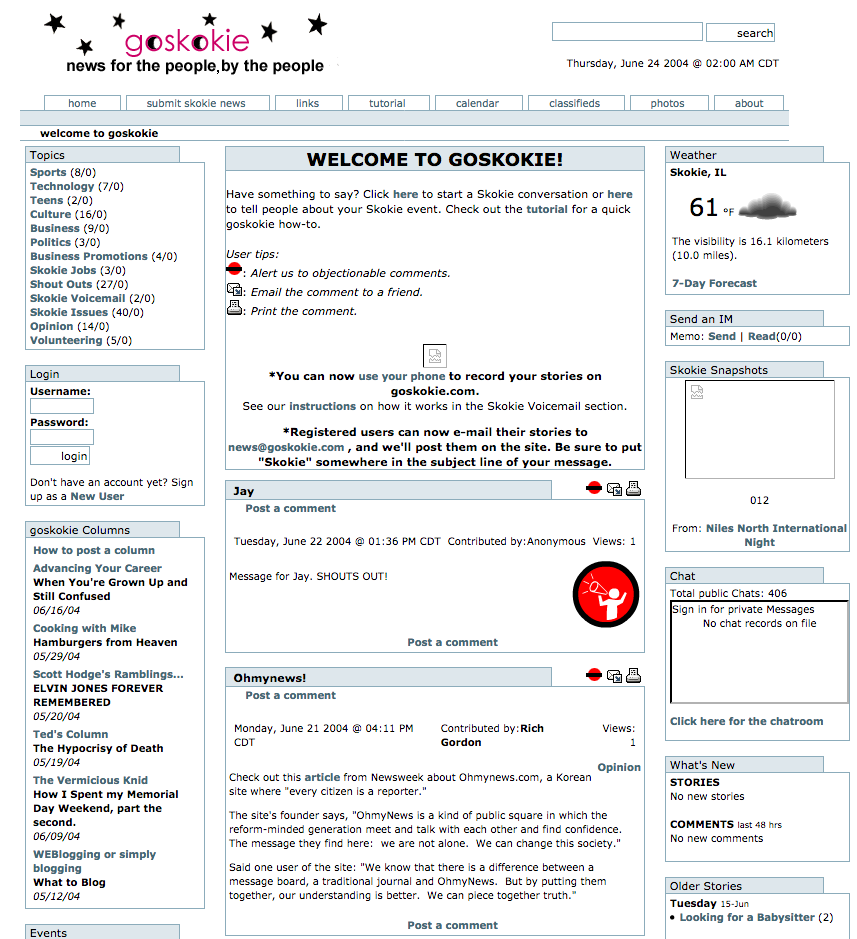

In 2004, a team of Medill School of Journalism grad students tried to save democracy, newspapers, and local communities. The threat? The internet. Our response? A website called GoSkokie for the people of Skokie, Illinois.

Yes, we thought we could use the internet to fix what was wrong with it. But with increasing social isolation, rising partisanship, and newspapers’ ongoing woes, it seems that the problems we hoped to solve with our shuttered project have gotten worse, not better.

Perhaps that’s part of the reason why, 14 years after the GoSkokie project, Google recently launched an experiment in local, user-generated storytelling: Bulletin.

Google suggested that Bulletin will enable people to “be the voice” of their community by contributing “hyperlocal stories,” but it appears to be struggling with getting people to participate during limited pilots in Oakland, Calif., and Nashville, Tenn.

Sounds familiar. We used the term Hyperlocal Citizens’ Media (HLCM) to describe GoSkokie, and we also encountered some of the difficulties Bulletin faces — despite the fact that things were a bit different in the GoSkokie era of 2004.

Back then, smartphones weren’t attached to people’s faces, and social media as we now know it didn’t exist yet. Friendster was founded in 2002 and MySpace in 2003; Facebook didn’t launch until 2004, and then only on college campuses.

Yet the idea of creating an open publishing platform related to geography remains intriguing. Most people feel strong ties to one or more places — cities, towns or neighborhoods. But most news sites don’t prioritize submissions from the public, and social media platforms hide nuanced local information inside obscure hashtags or private pages.

So the answer to these woes may still be “hyperlocal citizens media,” in which case our team’s findings and recommendations (PDF report) continue to be relevant. Here are eight highlights from our experience that could help the Google team behind Bulletin:

- Most average people don’t see themselves as reporters or information providers, so it’s easier to get people to visit a hyperlocal news site than to get them to become content contributors themselves.

- To maximize participation, offer multiple ways to contribute content. For GoSkokie, besides logging in and writing, users could contribute content via email and by calling a phone number and leaving a voice message.

- Specific topics — especially those already in the news — generate the most discussion and participation. In the case of GoSkokie, the firing of a high school teacher — covered in the local weekly paper — generated the most discussion on the site. It’s easier to build a discussion (and the potential for community connections) around an issue that is already on people’s radar screens than to conjure one up from nothing.

- Staff attempts to generate discussion will not work because they will appear to be inauthentic.

- A site that allows people to submit news items can turn out to be a valuable source of tips for journalists and established publishers. In the case of GoSkokie, one post (about a senior prank at the high school) ultimately turned into a Chicago Tribune story.

- Commercial messages — people promoting their businesses or using the site in ways similar to classified advertising — may be among the first kinds of content to be submitted. At GoSkokie, we chose to allow those kinds of posts, thinking that they could be of interest to users, but there is a risk that other kinds of content will be crowded out.

- Government institutions may see an HLCM site as an intrusion, nuisance, or threat because the site can give a voice to people who may not express themselves directly to elected officials. It is also a community forum the government has no control over. In the case of GoSkokie, one response from the village was a threatening letter contending that the topic icon we used for “Skokie issues” violated the trademark for the village logo.

- Google isn’t using content moderators, but GoSkokie showed how important they were to HLCM. They assured people that the site would not become a haven for vulgar and defamatory posts; served as a point person for working out technical kinks; and provided examples of participation that would inspire other locals to do the same.

These insights may not fit the product’s roadmap. Nor may they align with Google’s goals. The company isn’t required to do anything about the problems of journalism, democracy, and communal bonds. But with growing criticism of the tech industry, getting Bulletin right is in Google’s best interest. It should, as the Center for Humane Technology says, be “technology that protects our minds and replenishes society.”

We never overtly articulated a goal like that when we created GoSkokie, but many of our efforts and lessons learned reflected the importance of putting the community’s needs and preferences above our own. Done right, maybe Bulletin can bring people together and do something truly amazing: help make a world that doesn’t need it.